Welcome to the RV 101 Series! In this series, I briefly introduce you to all of an RV’s major parts and systems:

- Chassis

- House & Slides

- Cabinetry

- Appliances

- Electrical (AC+Generator and DC)

- Plumbing – Fresh

- Plumbing – Waste

- Hydraulic (opt)

Each post is a simple, non-technical introduction to how an RV works (and sometimes, why it doesn’t). If you’re new to this website, you should start here!

How Does an RV Electrical System Work?

An RV’s electrical system is made up of two sub-systems: 120-volt* alternating current (120VAC) and 12-volt direct current (12VDC). You can think of these as “shore power” and “battery power,” respectively. In general, 120VAC electricity is used for “big” electrical loads, like air conditioners, and 12VDC electricity is used for “small” electrical loads, like ceiling lights.

*You may see this referred to as 110, 115, 120, or even 125 volt service! For our purposes, they all mean the same thing.

The 120VAC “Shore Power” Side

The 120VAC electrical system is very similar to the electricity you’re accustomed to in your own home! It comes from the same power grid. But while a house is permanently connected to the grid, an RV must be temporarily connected with a flexible power cord to a campground power pedestal.

Bigger RVs need more power than smaller RVs. Therefore, almost all RVs are designed for either 30-amp 120-volt service or 50-amp split-phase 120/240-volt service. You can get a lot more power out of a 50A hookup than a 30A hookup!

(Don’t be confused by the “240 volts” of a 50-amp system. Technically, almost all RVs split the incoming power into a total of 100 amps at 120 volts. It’s confusing, I know, but that’s how the systems are named.)

RVers just call these “30-amp” or “50-amp” for short. Generally, 30-amp outlets or cords have three prongs or slots; 50-amp outlets or cords have four prongs or slots. That’s how you can easily decipher between the two types.

With the right adapter, a 30A RV can plug into a 50A power pedestal – or vice versa. With the right adapter, actually, you can plug any RV into any household outlet! – but you’ll be very limited in how much power you can draw.

Inside the RV, the 120VAC electrical system is very similar to your house. The feeder cable energizes a panelboard (also called a breaker box or distribution panel) full of resettable circuit breakers. From there, branch circuits run out to your household outlets, air conditioner, microwave, electric water heater, and other large appliances.

Any time you’re plugged into shore power, your RV’s AC electrical system should work similarly to if you were living at home! Just be careful to not overload the branch or feeder circuit, which will trip a breaker. RVs cannot draw anywhere near as much power as your house!

Common 120-volt appliances are:

- Air conditioner

- Microwave

- Electric water heater

- Household outlets

The 12VDC “Battery Power” Side

The low-voltage side of your RV’s electrical system is used for low-power electrical loads, like ceiling lights, the water pump, the furnace fan, and most appliance controls.

If everything in your RV ran off 120VAC electricity, you wouldn’t be able to do anything without being plugged in! 12V electricity makes dry camping and traveling much, much easier (and safer). For this reason, electric and slide-out leveling motors often also run off 12 volts, not because they are small loads, but because they can be operated without being plugged in.

Your RV has one or more house batteries that make up the main battery bank. If you have a motorhome, you also have a starter battery for your engine, but the two battery systems are normally not connected (unless equipped with a battery isolation/management system.)

These house batteries provide 12-volt power directly to your low-voltage loads. They are wired to a fuse panel, which is connected to individual DC circuits.

There is usually a battery cut-off switch and battery protection “shortstop” fuse between the fuse panel and the battery bank. You should learn where this switch and fuse are located.

Most appliances, even the “120-volt” ones like air conditioners, typically use 12-volts to run the control boards! You can think of the 120VAC electricity as the “brawn” and the 12VDC electricity as the “brain.”

Common 12-volt loads are:

- Lights

- Water pump

- Furnace (controls and motor only)

- 12V television

- Ceiling fans

- Stereo head

- Slide-out motors

The Middlemen: Converters & Inverters

The RV Converter

You might be thinking, “If my RV has a battery, don’t batteries need to be recharged? How does that happen?”

Great question! Almost all campers and motorhomes have a built-in battery charger called a converter. A converter then transforms some of the 120-volt AC electricity to 12-volt DC electricity.

A converter is commonly called the “heart” of your RV’s electrical system. It actually does more than just charge your battery. When you’re plugged into shore power, the converter directly powers all of the low-voltage loads. It’s a hardworkin’ device. Most batteries aren’t strong enough to power your RV’s DC loads without the help of a converter.

The RV Inverter

A device that has rapidly become standard in today’s RVs is an “inverter,” which is kind of the opposite of a converter. It works in the opposite direction: Turning 12-volt DC electricity into 120-volt AC electricity.

Remember, a converter charges the battery and powers the DC loads when you’re plugged into shore power. An inverter is useful for the opposite scenario: When you’re not plugged into shore power, an inverter discharges your batteries to power the AC loads.

Most RV inverters can’t power the entire RV. They usually only energize a handful of outlets and maybe your refrigerator. You would need a LOT of batteries and a GIANT inverter to run your entire RV off a single inverter! It’s theoretically possible but rarely practical.

Where Do the 120-Volt and 12-Volt Side Meet?

There are many, many options for wiring an RV! There is no one-size-fits-all answer.

In some cases, the AC and DC sides of the RV’s electrical system are kept physically separate. The DC fuses are located in their own panel; the AC circuit breakers are located in another.

In many RVs, the two are combined for space concerns into a master all-in-one power center.

Unfortunately, deciphering an RV’s electrical system is not an easy task! It befuddles many RVers and even residential electricians. Special training is required to understand all the ins and outs of the system.

What About the Generator?

If you have an onboard generator, your RV likely also has a transfer switch, which switches incoming power between shore power and the generator.

A generator is essentially a small engine connected to an alternator. It provides the same 120-volt alternating current as a shore power hookup, although the quality of the electricity is usually not as good.

Generators require fossil fuels to run, such as gasoline, propane, or diesel. On towables, generators usually have their own fuel tanks (unless they run off propane). On motorhomes, generators may draw fuel directly from the main tank.

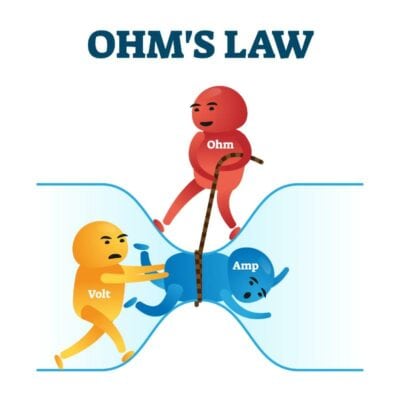

Bonus (Advanced): Ohm’s Law

If you want to begin to understand an RV’s electrical system, you must understand Ohm’s Law. In its simplest and easiest-to-remember form:

V = AR

- V = Volts (volts)

- A = Amps (current)

- R = Resistance (ohms)

This is the scalar form of Ohm’s Law used for simple DC circuits. For AC circuits, Ohm’s Law is only accurate with complex numbers, and R becomes Z for impedance, which includes both resistance and reactance. That’s far beyond the scope of this article (and website, for that matter).

A close (derived) relative is Watt’s Law, which gives us power as a function of volts and current:

W = AV

- W = Watts (power)

- A = Amps (current)

- R = Resistance (ohms)

Watt’s Law can be used to measure instantaneous and cumulative power requirements. Again, it is actually accurate when used with complex numbers, but in the simplified world of RVs, we can usually get away with using simple scalar numbers.

Voltage is akin to electrical pressure. It is the measurement of electrical energy carried per unit of charge. Just like water pressure, voltage “wants” to drive electric current from areas of high potential to areas of low potential. The earth is a convenient “zero point,” so we typically define electrical potential relative to the earth, with terra firma itself as “0 volts.”

Amps measure electrical current. They measure electrical charge per second. Amps are NOT the same thing as energy or power! They measure the electrical current from the charge carriers. Truly understanding what current is gets into the electromagnetic-field nature of electricity, which is beyond this website.

Resistance is whatever impedes the flow of electricity. It is measured in Ohms. Materials with low resistance, like copper, are conductors; materials with high resistance, like rubber, are insulators. Reactance includes the AC-specific effects of inductance and capacitance.

Power is energy over time. It’s a convenient and useful measurement for many electrical loads. We want to know how much power is being consumed or dissipated by that load at any instant. It’s measured in watts (more commonly in kilowatts).

Electrical circuits require a complete circular path for electrons to jump and for current to flow. (Mnenomic: electrons are always trying to go home). Technically, the electron charge carriers are quite slow, but the electric field moves almost at the speed of light!

Leave a Reply