I was recently working with a customer who wanted to retrofit and upgrade his mega teardrop camper (NuCamp TAB 400, Forest River R-Pod, Little Guy Max, that kind of a camper). He and his wife, both bon vivant chefs, enjoy steaming vegetables and sauteing home-cooked meals on their 2-burner propane range. They also live in this Lilliputian rig full-time, I might add.

So my customer – let’s call him “Grant” – asks me if we can install a range hood. “Sure,” I pipe up. “Not too difficult.”

Boy, was I wrong.

The Elusive High-Performance RV Range Hood

Half my battle was making a rectangular RV range hood fit inside of a tiny travel trailer with a curved roof and big acrylic sidewall windows and custom cabinetry, a place where everything looks like it drank the “Drink Me” shrinking potion from Alice in Wonderland.

But that’s not the half of the battle I’m here to tell you about. No, my axe to grind is over CFM: Cubic Feet per Minute.

You see, undercabinet RV range hoods come in two basic flavors: ductless (also known as recirculation) and ducted.

- Ductless RV range hoods are fancy purifiers. They recirculate air through a filter, usually an aluminum mesh version to catch grease. Nicer units also have an activated charcoal filter to adsorb smoke and odors.

- Ducted RV range hoods do a little more. Instead of just recirculating the interior air, they exhaust the air to the outside. Air in = air out, obviously, so the makeup air has to come from somewhere else in the RV, like an open window or drafty cracks around your entry door.

All conventional RV range hoods are undercabinet style, by the way. You won’t find island-style, downdraft, or inset (recessed) styles. (Furrion, if you’re listening! …)

Ducted range hoods have an ace up their sleeve. Because they exhaust air (and water vapor, aka steam) to the outside, they can control humidity. That was my customer’s main concern, you see. They weren’t too concerned about odors, but their steamed vegetables could turn their teardrop into a sauna. And a sauna, as you know, is the perfect growing place for mold. So ductless wasn’t an option.

I scoured the catalogs of multiple manufacturers: Furrion, GE, Greystone, Contoure, Ventline. I combed through dusty corners of the e-commerce web searching for a high-performance RV range hood that actually put out more air than a couple of computer cooling fans. And that’s not an exaggeration, by the way.

I came up empty. All the range hoods I could find – the 20, 22 and 24-inch models, the painted black or stainless steel models, the ones with aluminum grease filters and the ones with activated charcoal filters, the ones with dimmable light bulbs and fancy backlit switches – maxed out at 100 CFM. I even checked out range hoods for mobile homes. Zilch.

How Many CFM Does an RV Range Hood Need?

CFM stands for Cubic Feet (Per) Minute, and it’s a simple way of measuring how much air a fan can move. I’m no interior designer, but a quick Google search and a decent blog post informed me that the (residential) rule of thumb* is to divide the total BTU output of your stovetop by 100 to arrive at the minimum CFM for your range hood. A 2-burner Dometic stovetop has a main 7,200-BTU burner and a secondary 5,200-BTU burner. That’s a total of 12,400 BTUs, which means we need a minimum of 124 CFM.

*Take that measurement with a grain of salt, because if you look at even the smallest residential range hoods, they don’t come smaller than 200 CFM. The average size is 300-400 CFM, with high-performance models going all the way up to 1,200 CFM!

I’d trust those sample numbers before I trust the mathematical rule of thumb. A 10-inch pot on the boil on a 300-degree burner puts out the same amount of water vapor regardless of the total BTU output of the range. So even though the math only says we need 124 CFM for this RV, I think 200-300 CFM is the real minimum based on what the homeowners of America’s 144 million homes actually buy and use.

Another rule of thumb is to provide 100 CFM per linear foot. Under this rule of thumb, an 18-inch wide Dometic 2-burner stovetop would require 150 CFM … but again, I could not find a high-performance RV range hood that put out more than 100 CFM. (If you make one or know who sells one, please let me know!)

The Pain of RV Air Dehumidification

I’m afraid the conclusion to this story is rather anticlimactic. My customer and I batted about a dozen different ideas. Eventually, we settled on installing another 14×14” Dometic roof vent above the range in question – but then we scrapped that project due to concerns about A) roof rafter strength and B) interior cosmetics.

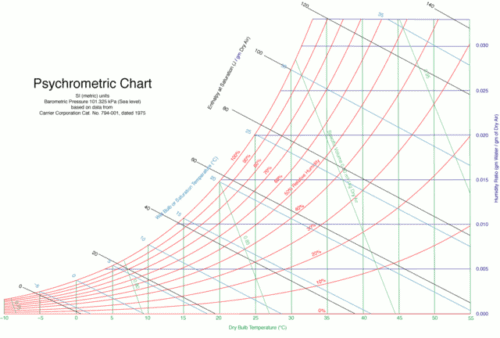

Conditioning interior air is surprisingly difficult. Many mechanical engineers leave school to go work in HVAC/R fields. Controlling the humidity, temperature, pressure, exchange rate, and cleanliness of the air we breathe is, erm, not as simple as it seems. It takes a labyrinth of fans, ducts, compressors, wires, and filters to make it all happen.

Here were some of my design challenges:

- Desiccants like DampRid simply don’t absorb enough moisture, or absorb it fast enough, to counteract the effects of steamed vegetables.

- Thermodynamic dehumidification (such as a rooftop air conditioner) requires a compressor to move the refrigerant. A compressor normally runs off 120-volt AC electricity, which is not always an option for RVs on the go.

- Adding an inverter so my customer could run his air conditioner (or portable dehumidifier) was outside our budget. These are power-hungry devices, which usually require at least 400-600-Ah of battery life and a 2,200-plus-watt inverter to match.

- Thermoelectric cooling and dehumidification technology (aka Peltier dehumidifiers) aren’t big enough to keep up with the air exchange in an RV.

- A whole-house fan (analogous to a simple powered roof fan in an RV) works well in a dry(er) environment, but air exchange alone can’t dehumidify an interior if the air outside is already warm and humid, which is common in the US Southeast. You typically need to be west of the Mississippi.

Grant and I worked through some of these options, but given budget and time constraints, none were chosen. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a high-performance RV range hood.

The most pragmatic solution I could offer? A pressure cooker.

Leave a Reply